The Lugubre Gondola

- Sephyra Clerc

- Feb 24, 2024

- 11 min read

Updated: Feb 28, 2024

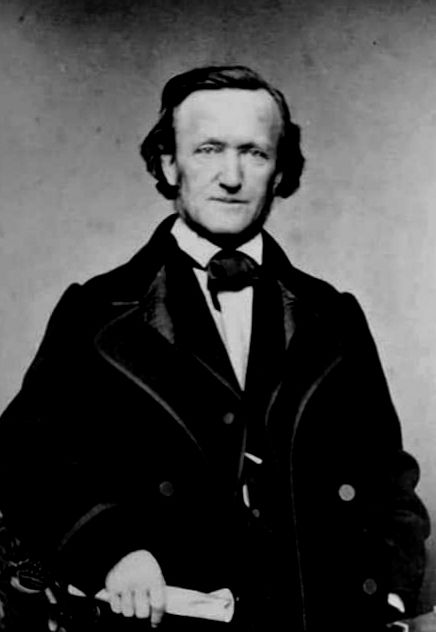

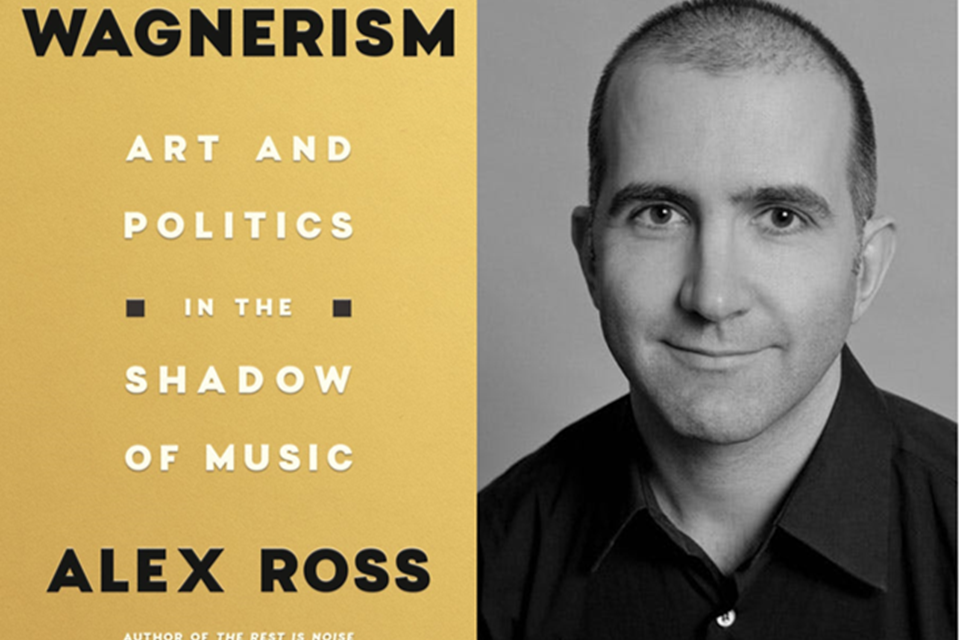

This month on the 13th marked the 141st anniversary of the death of Richard Wagner in Venice, at the Palazzio Vendramin Calergi. As I've said in a previous email I wanted to honour the occasion with a little post detailing the repercussions of Wagner's passing on the world of music and, more generally, the world of his time. In 1882 Franz Liszt, who was a guest of Wagner's at the Palazzio, started work on a piano piece now known as La Lugubre Gondola, which is striking as a premonition of the death of Liszt's longtime friend and beneficiary. It was in 1885, two years after Wagner's passing, that Liszt revisited the work and rewrote it for string orchestra, intending it, by that time, as a memorial to his deceased friend. The title was on the mark: Wagner's long funeral procession to Bayreuth began on a gondola that carried the body to Venice's Santa Lucia railway station, before being repatriated to Germany. But Liszt's tribute was only one among a gigantic amount of musical compositions, poems, odes, and other tributes to the deceased Bayreuth master, and it seems that mourning upon receiving the news extended to all countries in Europe, stretching even to the United States. Alex Ross, in his book Wagnerism, starts his work by giving an overview of the reaction of the world at Wagner's death. While fundamentally strange & incomprehensible at first pondering, this choice reveals the importance of the subject of Wagner's death to assess the importance of Wagner's life. The nature of Wagner's personality as a man and work as an artist gives death and annihilation a singular preponderance as themes of his life: it is not surprising, therefore, that the one most Wagnerian thing about Wagner's life was his death. The funeral procession that escorted his body back to his homeland was the funeral of a hero; the works created by artists of all sorts and poets all over the world to pay tribute to the passing of the revered "Bayreuth master" are truly worthy of a Viking funeral. The phenomenon which Wagner's death turned out to be not only in his native Germany but in the world and the mourning it extended among his contemporaries, give us an image, still today, of the extraordinary force of his presence and his influence among his peers. To this day his death is still the object of revisiting and commemoration, but it is impressive to delve deeper into the true significance of the phenomenon for the artists of Wagner's time. We're going to explore this a little bit more.

Richard Wagner's "Music of the Future" is an invention of the composer's detractors that is often misattributed to him. His concept of the "Artwork of the Future" is something entirely different that has nothing to do with the nature of music itself.

Beginning a text on the significance of Wagner's life with an account of Wagner's death makes a first statement: his influence on the world of art, and the power of his presence, were great enough to survive him into posterity, and leave his contemporaries with a feeling of lack and of loss. Algernon Charles Swinburne, the American poet, wrote in reference to the event:

"Mourning on earth, as when dark hours descend,

"Wide-winged with plagues, from heaven; when hope and mirth

"Wane, and no lips rebuke or reprehend

"Mourning on earth.

"The soul wherein her songs of death and birth,

"Darkness and light, were wont to sound and blend,

"Now silent, leaves the whole world less in worth.

"Winds that make moan and triumph, skies that bend,

"Thunders, and sound of tides in gulf and firth,

"Spake through his spirit of speech, whose death should send

"Mourning on earth."

Reporters all over the world and first of course in Italy, which had first received the news, mourned the event as a "thunder strike" and other such superlative words. And of course, Anton Bruckner dedicated his 7th Symphony, which he had started writing in presentment of his beloved friend and mentor's death, to King Ludwig II, Wagner's patron. The Adagio of the 2nd Movement is a long, remarkably beautiful song of mourning. Mahler's reported reaction upon receiving the news was to run through the streets like a madman, and answering a friend who asked him what was the matter, and whether his father was ill, he replied: "Much worse! The Master has died!" Giuseppe Verdi wrote a friend: "Wagner is dead! Reading the news yesterday, I was horror-struck, I can tell you!" Here's what the New York Times displayed: "The life of Richard Wagner affords a remarkable illustration of the results of persistent efforts in carrying out to its conclusion the inspiration of genius." And Alex Ross, from whom I've stolen all the aforementioned remarks, has written his own tribute in a few sentences worth quoting here:

"The global ceremonies of mourning in 1883 showed how immense a shadow Wagner cast on the world in which he lived. The truly extraordinary thing is that after his death the shadow grew still larger. The chaotic posthumous cult that came to be known as Wagnerism was by no means a purely or even primarily musical event. It traversed the entire sphere of the arts - poetry, the novel, painting, theater, dance, architecture, film. It also breached the realm of politics: both the Bolsheviks in Russia and the Nazis in Germany used Wagner's music as a soundtrack for their attempted reengineerings of humanity. The composer came to represent the cultural-political unconscious of modernity - an aesthetic war zone in which the Western world struggled with its raging contradictions, its longings for creation and destruction, its inclinations toward beauty and violence. Wagner was arguably the presiding spirit of the bourgeois century that achieved its highest splendor around 1900 and then went to its doom.

"He became the Leviathan of the fin de siècle in large part because he was never merely a composer. An idiosyncratic but potent dramatist, he wrote the texts for all of his operas, combining spectacular action sequences with intricate psychological studies. He was a prolific, all-too-prolific essayist and polemicist, whose menagerie of concepts - Gesamtkunstwerk ('total work of art'), leitmotif, 'endless melody,' 'artwork of the future' - overran intellectual discourse for several generations. He was a theater director and theorist who reshaped the modern stage. Productions at his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth anticipated the advent of the cinema, conjuring legends in the dark. Finally, and fatally, he dabbled in politics, helping to popularize a pseudoscientific form of antisemitism. The sum of all these energies cannot be fixed. 'The essence of reality lies in its endless multiplicity,' Wagner wrote in 1854. 'Only what changes is real.'"

And Alex Ross also writes in his introduction: "This is a book about a musician's influence on non-musicians - resonances and reverberations of one art form into others. Wagner's effect on music was enormous, but it did not exceed that of Monteverdi, Bach, or Beethoven. His effect on neighboring arts was, however, unprecedented, and it has not been equaled since, even in the popular arena. He cast his strongest spell on the artists of silence - novelists, poets, and painters who envied the collective storms of feeling that he could unleash in sound."

I recommend Alex Ross' book to anyone interested in getting a valuable perspective on the impact of Wagner on posterity, not only as a musician, but on all the arts.

I've quoted hugely from Alex Ross, and perhaps this blog is more of a theft of ideas than anything else. But as I said above, the aim of this post is not to explore Wagner's life but his existence after his death, into posterity; and in order to explore that, no better source is available to the writer, than the accounts & testimonies of eyewitnesses and contemporaries. Alex Ross' work is not entitled Wagner, but Wagnerism; and as suggested by this, his book is less about Wagner the man, than about his ghost wandering into the world after his death - that is, his reach into posterity. This points to one important and quite unique fact about Wagner: his singular tendency as an artist to give birth to ideas that survived him and took on a life of their own. His influence on the arts was so strong, that its shadow kept growing after his death, and extended to even more areas, and gained more ground than in his lifetime. The artistic society of the 20th century was largely a product of his innovations, his theories, and his presence in the domains with which he dealt. He was a man who wrote an essay out of a simple idea; just as he seemed to have a theory for just about anything that crossed his field of scrutiny, so he deemed it necessary to endlessly explain himself to his audience in writing and theorizing. His energy & inspiration still from today's point of view appear inexhaustible: nothing was too big for his ambition, his almost compulsive need for creative endeavour, and among composers he has certainly left us with the most gigantic amount of literature not only on the original subject of Art, but on many other themes on which his need for argumentation branched out. In Wagner one feels an irresistible urge to make a point, to reason out of something which has not been reasoned out before, to create new paths of thought that reform a way of thinking deemed obsolete. And it is precisely because of this that Wagner the writer is as important to consider as Wagner the composer.

Wagner's funeral procession in Bayreuth, on February 18th, 1883. A gondola carried his body via the Grand Canal to the railway station in Venice from where it was transported back to the composer's homeland.

To illustrate what I mean by "compulsive need for creative endeavour," I think nothing will give a better example of it than taking the case of Wagner's most controversial and perhaps most famous work: the Ring Cycle. When Wagner started work on the epic poem that was later to become the libretto of the Ring, his friends, seeing the scale of the work, attempted to discourage him from carrying out his project; but as said Henry Simon, who wrote 100 Stories of the Great Operas, he indeed persisted not only in the completion of the great work, with text and music, but he had a theatre built expressly for the performance of this one work, a theatre in the construction of which he fully participated. In fact, Wagner's dedication & rock hard obstinacy to have his way can't be understood without delving deep into what he believed in as an artist, his personality, and perhaps the story of his life. His commitment to his ideal has appeared as fanaticism, bigotry, and all sorts of other things to downright lunacy to his detractors. Fans (called "Wagnerians" or "Wagnerites") hail him as a genius whose artistic integrity allowed him to pursue a vision with a steadfastness & energy beyond that of ordinary mortals: they see his very work and the tremendous success it achieved as proof that he was indeed a visionary.

But in fact none of these views seems totally relevant in the present century, when all we've stolen from the inspiration of our predecessors we take for granted. Numerous innovations brought forth by the master of Bayreuth actually heralded or even inspired some of the modern artistic techniques in music, cinema or the visual arts: but taken objectively, there are also a lot of things which didn't happen as he planned - indeed, most of them. Debussy said Wagner's music was "a beautiful sunset that was mistaken for a sunrise." And as a matter of fact when we look at Wagner's great work it seems to stand unique in its kind, to still hold its sway now as it did in his own lifetime: and if it seems to be thus, it is because, as so many have pointed out, the composer of the Ring left no successors worthy of him, or rather, capable of continuing his endeavour into posterity. He had views too unique, too absolute, a vision too grandiose and too precise of just what Art should be, an impossible mix of all his own very complex ideas and philosophical meanderings, to transmit them to a later generation, which would ever regard them as the extravagances of an over-philosophizing musician who'd have done better to remain just a musician. For his part, he seemingly cared little about what others thought of him, since after all, he identified himself not with the other composers of his own time, his peers, but with the contemporaries of Dante, Aeschylus, Beethoven, and all the greats of times past.

The two philosophical influences of Wagner: Ludwig Feuerbach, (top) the early mentor, and Arthur Schopenhauer, (bottom) the later revelation, portrait by J Schäfer, 1855. Wagner never considered himself as his contemporaries' peer: he was the equal of Dante, of Aeschylus and of Goethe.

The true question then, is this: would Wagner have been such a composer had he not been also a philosopher, and, in more general fashion, the man that he was? The question of fame & success seems obsolete; even in his time, the Bayreuth master was never a popular or successful composer - there has always been too much controversy around him, his ideas, his deeds, and whatever latest essay he came up with. It seems it was Wagner's aim in life to create controversy, to provoke thought, to change people's minds, to challenge their view of reality, when his own seemed so set and yet so vast. And so, in the light of those considerations, it seems ill-termed to say that Wagner was a visionary, as his fans say, or that he was a madman and a fanatic, as claim his detractors. He was imbued with his own sort of fanaticism, and his own vision; in fact, he himself created what he was: as said Henry Simon, he was the first Wagnerian, and the greatest of them all. One recalls the words of Brahms, perhaps Wagner's most famous enemy, when writing to a friend: "This morning I awoke at the song of a lark out the window: it reminded me that not everything in the world is by Wagner." I am paraphrasing - I was never able to find the quote again - but the phrase is eloquent however it is said.

Nor is Wagner's fate something which he would particularly have regretted, or so it seems. After all, his work was always about destruction, a world running to its doom - not only the world of power of the Niebelungen, but also that of the gods, and an entire community that linked men to gods and heroes to common mortals: all collapsed under the monstrous weight of collective egoism, lust for power, greed, and all human vices imaginable. In that perhaps Wagner was also the greatest visionary of them all. But the perpetual doom & destruction that hold sway everywhere in his colossal oeuvre have taken their toll, or so it seems: for his vision & his works have started running to their doom from the very moment when they were created, and have done so ever since - first in the historical dramas which they came to represent, and then as they kept taking on a mysterious life of their own long after their creator's death. There is constructive & destructive magic in Wagner's work, and they tragically equate each other, so that now nearly a century and a half after his death practically no progress has been made in the true interpretation of the meanings behind his masterpieces. And thus as has been said he was not exactly a visionary, and the greatest flaw in his work is perhaps to have been too out of step with collective thought. Nor was he a madman or a lunatic, as he is dubbed by his detractors: the universally recognized genius of his works is proof to this, although it will perhaps never emancipate itself from the controversy that has forever surrounded it. At the end of the day, none of this truly matters, because whatever prevails, we'll always be fascinated by the artist and the man Richard Wagner, with his flaws, his genius, his incredible energy and artistic inspiration, his integrity as a musician, a poet and a philosopher, and the greatness of his work, the magnificence of his vision, the commitment to which he adhered with a discipline incomprehensible to us now, will always haunt our minds and make shimmer before our eyes visions of a world not

our own, that seems to stand somewhere and sometime, ready for us to conquer.

Max Brückner's 1894 depiction of the Twilight of the Gods from Wagner's opera Götterdämmerung. Wagner's music presents us with an epic spectacle of glory & decadence, creation & destruction, that are tragically intertwined.

Wonderful article, I do hope many will read it. I am, a Wagnerite, I enjoy learning about so many that share their knowledge about the great composer and those who followed and admired him and composed master pieces in his honor. Thank you.